Every flight should teach you something… Any time we go flying there is plenty we can learn; but occasionally there are flights that offer a variety of lessons for an inquisitive pilot. The private pilot license is a license to learn, active pilots build skills because they exercise the privileges of their pilot certificate.

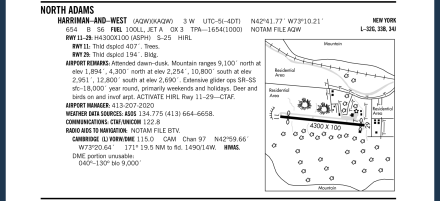

The summit of the highest natural point in Massachusetts, Mt. Greylock, within five miles of the North Adams airport. The summit of Mt. Greylock is 3,491 ft. and the elevation of the North Adams airport is only 654 ft. Quite the difference!

Billy Smith is a great example of this open-minded and active type of pilot who goes out to fly and learn each time he takes off into the wild blue yonder… I met Billy at Bridgewater State University, where he was a member of the Aviation Marketing Management course I taught this past spring semester. He is an instrument rated private pilot, and he is at the tail end of his commercial pilot training, with plans to begin working towards his flight instructor certificate immediately following his commercial pilot check ride.

Billy stood out as a member of that class based on his superior performance, and when he offered to write a piece for ReviewBeforeFlight, I was more than happy to accept it. His only direction was that it should be aligned with the type of content we offer here on RBF. Read on to see his review of a recent flight… He does a great job explaining conditions and situations he faced, how he handled them and what lessons he took away from each of these. This is a fantastic and very effective technique that I’d recommend for any and every pilot to maximize the experience and learning from each flight they make.

Turbulence Terrain and Traffic

By: Billy Smith

It was a warm and windy summer afternoon in Massachusetts, and I was ready to land a Cessna 172 after a routine two-hour solo flight. My destination was KAQW, North Adams MA, right in the Northwestern corner of the state. I had taken off from KEWB, New Bedford, MA and had stopped to practice my commercial syllabus landings at 7B2, Northampton, MA. It was my first time flying out to the Western portion of the state, and my first experience of shear horror on a solo flight.

After completing my spot-on practice landings at Northampton, MA, I departed the pattern and set power and heading for my pioneering journey towards the Western mountains of Massachusetts, the Berkshires. As I began to arrive on the gradual eastern foothills of the Berkshire mountain range, everything was going smoothly until the plane began to shake. I noticed the plane was beginning to hit some mild turbulence. I brushed it off, and thought it might be late-afternoon updrafts. However, after a few minutes of mild bumps, the turbulence began to get stronger and stronger. After about ten minutes of flying over the more elevated, and jagged terrain, I began to experience constant turbulence. The turbulence became strong enough, that it was tossing my belongings across the cabin, into exotic locations I had forgot existed. To get out of it, I climbed a few thousand feet, but it still didn’t fully rid the turbulence. Getting closer to my destination, the turbulence began to let up, and I was able to smoothly gather a strong and steady grip of the aircraft’s flight path. (A hypothesis on this later in the article)

After battling the jolting turbulence through the beginning of the Berkshires, I finally arrived within the vicinity of my destination. Winds were out of the west at the field, almost straight down the airport’s only paved strip 11-29. AQW is mounted in the Hoosic River Valley between a shallow sloped mountain, Eastern Mountain -to it’s North; and to it’s South, the largest mountain in the state of Massachusetts, Mt. Greylock -sitting at 3,491 feet. Upon arriving within the vicinity of AQW, I was greeted by several voices over the CTAF. I thought this was highly unusual considering the remote area I was flying to, and my (perceived) unpopularity of the airport. I began my entrance to the area via the Eastern portion of the Hoosic River Valley, when I quickly began to realize, this was not going to be easy. To my dismay, I had left out a very important task in flying to an unfamiliar airport during my pre-flight planning, and that is to check to see how to enter the airport’s traffic pattern! I assumed, that upon arrival at this airport, I would simply enter it’s traffic pattern, then breezily make my way into a picture perfect downwind and final approach. Well, reality gave me an excellent wake up call that day, and completely changed the way I confront my pre-flight planning. (Especially to mountainous areas)

As I preceded closer to the airport, my radio was flooded with new position reports of traffic coming into land on runway 29. All of the planes were using the left downwind and base to runway 29. The only problem with this, is that Mt. Greylock is so close to the airport, that the only way to enter the left downwind is to approach it through the Western portion of the river valley, and directly enter the left downwind parallel to runway 11’s right side. Because I was coming from the Eastern side heading west, to enter the pattern on a 45 left downwind would be impossible without clipping trees on the slope of Mt. Greylock. Being wedged in a Valley gave me little room to turn around and do a 360 turn for spacing. My only option would be to climb over the field and all the planes coming in to land, or to approach runway 29 head on, turn to the right, and enter the left downwind by flying over the field then immediately turning left. I was in a tight squeeze.

While I strategically began my non-standard entry to the field, the traffic on downwind, base, and final were beginning to wrap up their patterns, and coming in for smooth landings. Even though the planes were so close to each other in the pattern, their radio calls were eerily calm. Normally everyone at an uncontrolled field has a stressed, or uneasy tone of voice, because of the high stakes situation the pilots are in. However, these men behind the radios were relaxed and laid back! After calling each other’s tail numbers out like they had originally been doing, they started calling each other, “Jim!” “Bob!” “Dave!” It was obvious these guys knew each other, and had done this same landing sequence before. I announced my intentions of swinging to the right of the airport to do my turn, and then swing into the left downwind for a landing. As I got to the North side of the field, the traffic on final landed. The only thing was, it landed on the grass next to the runway. I looked closer at the other traffic, and began to realize none of these planes had engines, they were all gliders! When making my calls on the radio, they kept referring to me as “that guy”, not a Cessna, nor a white plane, nor my tail numbers, I was “that guy!” I knew this place would be an alien planet compared to what I was used to. I feel like I was one of the only outside airplanes to land at this airport in a while. Maybe there was a good reason for this?

By this point I am directly over the center of runway 11-29, and ready to make my entry into the left downwind for runway 29. After listening to the CTAF closely, I have come to the conclusion that all three of these glider pilots have either landed their plane, or about to do so, as they have quit yapping about what kind of steak they are going to grill when they get on the ground. I make my position report, then begin my left hand turn. I look out my right window. Taking up the entire view of my right window is a little red glider sailing carelessly on downwind. I let out a loud “Yelp!” then made an immediate evasive turn in the opposite direction to narrowly avoid getting nailed by a floating piece of fiberglass. My stomach turned upside-down, my heart was ready to beat out its ribcage. What was this guy doing!? How could I not see him!? Does he have a radio!? Did I mess up!? Many questions raced through my mind. My only concern was to get on the ground ASAP safely.

I made a left 360 turn over the airport. With my hands shaking, I made another position report. Once again, no answer. I followed the rogue glider that nearly ended my flight on downwind, base, and final. He landed on the grass strip, and I landed on the runway. I back-taxied, then parked near the other planes. I did my ground check, and shut down the rest of my equipment. I exited the airplane, thinking I had done something terribly wrong. Despite the breathtaking view in every direction my eyes laid, I was shaken up, and felt like the near mid-air collision was all my fault. I walked over to the little red glider, and approached the little old man who had just flown it. I said, “Sorry about that! I didn’t see you when I entered downwind!” To my astonishment, the old man said this, “I saw you the whole time! –We were miles apart!” Bewildered, I took a step back, collected my thoughts for a moment, and then blurted, “Did you hear my radio calls? I made lots of them!” The old man said, “Yes I heard you. It’s just that I saw you the whole time, so I didn’t need to make calls.” Even though I felt a large sense of relief, I was still puzzled how an experienced gentleman could make such a reckless decision. I stayed at the airport for about an hour to relax and take in the picturesque view of the valley, along with Mt. Greylock and it’s peaks. I called the briefer, then shortly after lifted off from North Adams on my way to my next destination.

Lessons Learned:

We’ll start with the beginning of this short story, turbulence. Throughout the beginning of the flight turbulence was not an issue. Why is it when I arrived at the eastern foothills of the Berkshires, did I experience turbulence? Why didn’t I experience heavy turbulence as I went further into the mountain range?

Here is my hypothesis:

As I approached the eastern edge of the Berkshire mountain range, I was on the leeward side of the mountain winds. Because fluids (like air) enjoy taking the path of least resistance from high to low, they find stability in straight lines. However, if you shove something in its way, like a mountain, it will become disturbed. The rippling unstable air that follows a mountain peak is a direct result of disturbing smooth airflow. The same thing would happen if you stuck your hand in a smooth flowing creek. The fluid behind it would be unsettled, and have a chaotic motion behind it.

Why then, did turbulence ease up as I got closer to the Western side of the mountain range?

This is the result of flying further upwind from the origin of the disturbance. If you have a line of mountains continuing downwind, you are going to have a build up of unstable air. As I arrived further upwind in the mountain range, there was less of a build up of unstable air, making the flight much smoother than the eastern side of the range.

Did either pilot of the glider or I make any illegal actions to compromise safety?

The key word to this question is legal. Yes, we both definitely made mistakes and we both learned from them. However, nothing we did was illegal. According to FAR 91.126, all turns in an uncontrolled traffic pattern must be to the left, unless otherwise specified. However, a pilot has the discretion to fly whatever leg he so chooses at an airport. So basically, although not preferred, a pilot can legally fly whichever entry to set up a landing that he chooses. Unfortunately, this happens all the time, even at airports pilots are highly familiar with. According to the AFD, the airport has no restricted left or right patterns. This means, even though Mt. Greylock will prevent an entry to the left 45 downwind from an eastern approach, the AFD doesn’t include that in their remarks. It is the pilot’s ultimate responsibility to plan accordingly for how they will set up their entry to the field’s pattern. The AFD is not responsible for doing it for you. In this case however, they do show the boundary of Mt. Greylock to the South.

-To correctly enter this pattern, a pilot must either approach the airport from the West, or overfly the airport from the east, and then descend to enter from the west.

As for the glider pilot, he had the right to remain silent over the CTAF. Even though pilots are not required to make position reports over the CTAF, it is very highly recommended. If I had known where he was I wouldn’t have had such a close call with him in his glider. Adding on to his reckless decisions, was his macho attitude about foreign pilots entering his field. The band of glider pilots were flying in the valley with their wives and friends on the ground making BBQ’s and playing horseshoes. One of the wives was actually mowing the airport lawn when I arrived on the ground. It seems like this group of glider pilots believes; because this public use airport is not frequented by outsiders, they can use it like it is their own privately owned airport and run it like it is their own privately owned airport, too. I’m sure this isn’t the only airport in the country that is treated like this –there are most likely many small airports in the nation with this attitude.

What tools can a pilot use to plan for mountain flights?

Another important lesson a pilot can take away from this is: when flying to unfamiliar mountain airports, check the topography of the region before you attempt to enter the field’s traffic pattern. Some very helpful tools for this are topographic maps, which tell you the height, and slope gradient of terrain in the surrounding area. Another excellent resource is Google Earth. This application lets you hone in anywhere on the planet, and look around from any vantage point in 360 degrees. However, I think the most valuable resource for a pilot flying into a mountainous area would be to use a virtual flight simulator, such as Microsoft Flight Simulator, or Xplane. These programs allow you to fly the same approach to landing that you would do in the real plane, so you can virtually see what approach paths work for you and what do not. You can also set the wind speeds and ceilings to match the exact scenario you may be confronted with.

Take a look at the terrain before you go flying. This image is from http://www.verticalstudios.com and if you’ve never heard of them or haven’t visited their website, check it out – they have some great stuff to help pilots!

Thanks for reading my article! Fly Safe, Billy.

Pingback: A Unique Opportunity Seized… | The Review Before Flight Blog